|

This is a great overview of people who get cancer and struggle at their workplace. It is important to know your rights and responsibilities. There are enough stressors in life, after a diagnosis of cancer - than to struggle with the complexities of keeping a job.

https://www.theaustralian.com.au/commentary/editorials/cancer-patients-workplace-rights/news-story/9fdf6b58af8da3be792eb098a54e55a0 - EDITORIAL Among 150,000 Australians who will be diagnosed with cancer this year, many will be in the workforce. They will have families to support and financial commitments. Many will need time off for treatment and will be relying on sick and long-service leave. Extended illnesses among staff can create problems, especially for small businesses. Goodwill and flexibility on both sides help. Much depends on the severity of the illness, the treatment and the practicality of options such as working part time or from home. Many patients recover and return to work for decades. Liz Tapping, 56, a Melbourne mother of three who was sacked after she asked to take personal and annual leave for breast cancer surgery and treatment, has made an important point for those forced to quit their jobs in such circumstances. At the hospital, she was told she could continue to work and juggle her treatment around it. And the company accountant told her she had accrued holiday and sick leave to cover her absence. But after she lost her job in 2019, she decided to fight her dismissal. She reached a financial settlement with her employer, Empress Diamonds, after the Federal Circuit Court found the company contravened the Fair Work Act by terminating her employment because she proposed to exercise her rights to take leave. Her situation is not unique, advocates for women with breast cancer told workplace editor Ewin Hannan. Breast Cancer Network Australia policy, advocacy and member support director Vicki Durston said employers faced a complex situation when employees were diagnosed with cancer. The problem was often a lack of understanding, and lacking the resources and tools to understand how to tackle the challenge of one of their employees having a cancer diagnosis. Cancer patients do not need the stress of fighting for their rights in court. Neither do businesses. Ms Tapping’s illness has returned, sadly. But lessons can be learned from the stand she took and from the outcome. As Ms Durston says, the issue for employers is “about making sure that you have the conversation with your staff, and you understand what this means and knowing your rights”. This article is an article from the USA, but the principles remain the same. I like to offer a referral to the Palliative care community services, fairly early in the diagnosis of metastatic cancer. The support from the Community Palliative care nurses is invaluable. There are a range of extra services which can be accessed, including Advanced Care Directives, legal paper work, etc.

Palliative care referrals in Australia are not just for end-of-life care. It is worth discussing with your doctor. Supportive care, started early, will improve more lives BY LYDIA DENWORTH https://apple.news/AVmTHvsveRjWvAaA-UEAyQw IN THE LAST months of my mother’s life, before she went into hospice, she was seen at home by a nurse practitioner who specialized in palliative care. The focus is on improving patients’ quality of life and reducing pain rather than on treating disease. Mom had end-stage Alzheimer’s disease and could no longer communicate. It was a relief to have someone on hand who knew how to read her behavior (she ground her teeth, for instance, a possible sign of pain) for clues as to what she might be experiencing. I was happy to have the help but wished it had been available earlier. I’m not alone in that. Evidence of the benefits of palliative care continues to grow. For people with advanced illnesses, it helps to control physical symptoms such as pain and shortness of breath. It addresses mental health issues, including depression and anxiety. And it can reduce unnecessary trips to the hospital. But barriers to access persist—especially a lack of providers. As a result, palliative care is too often offered late, when “the opportunity to benefit is limited,” says physician Kate Courtright of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. In 2021 only an estimated one in 10 people worldwide who needed palliative care received it, according to the World Health Organization. In the U.S., the numbers are better—the great majority of large hospitals include palliative care units—but it’s still hard for people who depend on small local hospitals or live in rural areas. Outpatient palliative care is especially hard to find. Experts are also working to correct misconceptions. “When people hear the words ‘palliative care,’ they think ‘end-of-life care—I’m going to die,’ ” says physician Helen Senderovich, a palliative care expert at the University of Toronto. Although palliative medicine grew out of the hospice movement, it has evolved into a multidisciplinary specialty encompassing physical, psychological and spiritual needs of patients and their families throughout the trajectory of disease, Senderovich says. That path includes the time when treatments are still being tried. So palliative care specialists have begun referring broadly to “supportive care”—“anything that is not directly modifying the disease,” says medical oncologist and palliative care specialist David Hui of the MD Anderson Cancer Center. For example, wound care and infusions to improve red blood cell counts in cancer patients are supportive; chemotherapy is not. Generally, the earlier that supportive care is offered, the more satisfied patients report feeling. And ideally, people who need it now get referred to palliative medicine around the time they are diagnosed with a serious illness. An influential study in 2010 found that patients with lung cancer who received palliative care within eight weeks of diagnosis showed significant improvements in both quality of life and mood compared with patients who got only standard cancer care. Even though those receiving early palliative care had less aggressive care at the end of life, they lived an average of almost three months longer. More recent studies have confirmed the life-quality advantages of earlier palliative care, although not all studies have shown longer survival. “Patients don’t just start having pain and anxiety and weight loss and tiredness only in the last days of life,” Hui says. Starting palliative care earlier allows patients and the care team to “think ahead and plan a little bit,” he adds. Nor is palliative care effective only for cancer, although that’s where much of the research has been done. It benefits those with heart failure, chronic kidney disease, dementia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), Parkinson’s, and other serious illnesses. In January 2024 the Journal of the American Medical Association published a pair of studies that broke “new ground” in developing sustainable, scalable palliative care programs, according to an accompanying editorial. One, the largest-ever randomized trial of palliative care, included more than 24,000 people with COPD, kidney failure and dementia across 11 hospitals in eight states. The researchers made palliative care an automated order, where doctors had to opt out of such care for their patients instead of going through an extra step of opting in. The rate of referrals to palliative care increased from 16.6 to 43.9 percent, says Courtright, lead author of the study. Length of hospital stay did not decline overall, but it did drop by 9.6 percent among those who received palliative care only because of the automated order. The second study looked at 306 patients with advanced COPD, heart failure or interstitial lung disease. Half these people participated in palliative care via telehealth visits with a nurse to handle symptom management and a social worker to address psychosocial needs; the other people in the study did not get such care. Those who received the calls quickly showed improved quality of life, and the positive effects persisted for months after the calls concluded. Because there are not enough palliative care providers, Hui advocates for a system that directs them to patients who would benefit most. Usually, and not surprisingly, those are people with the most severe symptoms. This system uses early screening of symptoms to identify these people. Hui calls the approach “timely” palliative care. “In reality, not every patient needs palliative care up front,” Hui says, so timely care uses scarce resources as effectively as possible. I don’t know exactly when my mother needed to start palliative care, but I hope that going forward more caregivers and more families know to ask about it sooner. ⬣ Lydia Denworth is an award-winning science journalist and contributing editor for Scientific American. She is author of Friendship (W. W. Norton, 2020). This is an article published in the TIME magazine. The majority of the data and links are US based, but the principles remain the same.

An expert panel in the U.S. says women should begin mammogram screening at age 40—a decade earlier than previously recommended. ALICE PARK IS A SENIOR HEALTH CORRESPONDENT AT TIME. SHE COVERS THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC, NEW DRUG DEVELOPMENTS IN CANCER AND ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE, MENTAL HEALTH, HIV, CRISPR, AND ADVANCES IN GENE THERAPY, AMONG OTHER ISSUES IN HEALTH AND SCIENCE. SHE ALSO COVERS THE OLYMPICS, AND CO-CHAIRED TIME'S INAUGURAL TIME 100 HEALTH SUMMIT IN 2019. HER WORK HAS WON AWARDS FROM THE NEW YORK PRESS CLUB, AND RECOGNITION FROM THE DEADLINE CLUB. IN ADDITION, SHE IS THE AUTHOR OF THE STEM CELL HOPE: HOW STEM CELL MEDICINE CAN CHANGE OUR LIVES. Most women should start mammogram screenings for breast cancer at age 40, and get screened every other year until they reach age 75, according to new recommendations from an expert panel. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), which is an independent group of experts funded by the government, regularly reviews data and makes recommendations on health issues, and many health providers follow them. It decided to revise its advice on mammogram screening that was last issued in 2016. That guideline said women should start regular mammogram screening every other year beginning at age 50, and that women ages 40 to 49 should discuss with their doctors the best screening regimen for them. Here's what to know about the latest change. When should most women get their first mammogram? The new recommendation is based on additional evidence that has emerged since 2016, says Dr. John Wong, vice chair of USPSTF. According to data from the National Cancer Institute, the rates of breast cancer for women in their 40s began increasing by 2% annually in 2015, and that trend justified a change in the recommendations to start screening a decade earlier. “Our current data shows that this recommendation could potentially save as many as one out of five women who would otherwise die if they waited to be screened until they were 50,” says Wong. “That’s potentially saving 25,000 women from dying of breast cancer. We think that’s a big win.” Dr. Maxine Jochelson, a radiologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, says the revision is long overdue. “The data have shown for years that by not screening women between ages 40 and 50, if women in that age group develop breast cancer, they are more likely to need chemo, more likely to need larger surgery, and more often get more aggressive cancers," she says. "I think they are late to the party.” It's not clear what is contributing to increased risk among women in their 40s. But Wong says the task force analyzed whether USPSTF’s recommendation around that time—to start mammograms once women turned 50 rather than 40, as the group's previous guideline advised—was a factor, as some advocates had warned. “Screening rates remained consistent throughout that period,” he says. “So that’s not the cause.” The most recent data do include different populations of women, however, incorporates different types of screening and treatment options that weren’t available when the previous populations were studied, so more screening may be leading to more diagnoses, for example. The current recommendation now brings the USPSTF’s guidance more in line with that of other health groups including the American Cancer Society. That group advises women to start screening at age 45 annually until age 54, then every other year. Why did the recommendation change? Wong says the new guidelines reflect the changing benefits and risks of screening and its consequences, which include additional testing, as well as the risk of false positives. The increased risk of breast cancer among women in their 40s tipped the balance in favor of beginning screening earlier. What about women with dense breasts? About half of women in the U.S. have dense breast tissue; for them, mammograms are less reliable at detecting cancer. The task force is less clear about whether these women should follow the same recommendations. It says the evidence supporting the benefits of additional screening—with MRIs or ultrasounds, which doctors often recommend if mammograms are negative or inconclusive—isn’t “sufficient.” Wong says more research is needed to understand if those additional imaging tests help women to get diagnosed earlier and ultimately allow them to live longer. “We just don’t have clear evidence at this time,” he says. Will insurance cover mammograms starting at age 40? All insurance companies (with few exceptions) must cover the cost of mammograms with no co-pay for women who get them as part of regular screening beginning at age 40. That’s part of the Protecting Access to Lifesaving Screenings Act that was passed by Congress in 2019. Because of this act, the new guidelines should not affect insurance coverage of mammograms for women in their 40s. But since the task force says the evidence for additional screenings is "insufficient," women with dense breast tissue may still have to pay out of pocket for additional tests beyond a mammogram. That could lead to lower follow-up for these women and ultimately may delay any breast cancer diagnoses until later stages, when the disease is harder to treat. “We worry about what it means for access and utilization for those women, to say that there is inconclusive evidence to support supplemental imaging,” says Molly Guthrie, vice president of policy and advocacy at the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation. Guthrie notes that already, many states require that mammography centers notify women if they have dense breast tissue, so they and their doctors are aware that the mammogram readings may have missed potential red flags for cancer. That requirement will apply to all mammography facilities beginning this September, after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which regulates the facilities, issued a new rule last year mandating the information. “The FDA is trying to get to the point of pushing the conversation about dense breast tissue so women have a dialogue with their providers,” says Guthrie. “But if you are not doing anything to change coverage, you are not going to increase utilization." Wong stands by the task force’s conclusion, seeing it as an invitation for further study. "We would love to have sufficient evidence that would help women with dense breast tissue to live longer, healthier lives, and we are urgently calling for more research to obtain that evidence,” he says. “We always look at the latest and best science—and at the benefits and harms—to make recommendations that help people in this nation stay healthy and live longer.” Correction, April 30 The original version of this story mischaracterized the increase in cancer deaths among women in their 40s. The incidence of cancer, not the death rate, has been rising at 2% per year. Oestrogen/Estrogen is one of the main hormones protecting the bones. As we reach menopause - the Oestrogen/Estrogen production from the ovaries ceases. The cessation of Oestrogen/Estrogen starts to affect the metabolism of the bones with calcium and others. Over time the bones get weaker, leading onto osteopenia and then osteoporosis.

The main risk of osteoporosis of fractures of the bones. Women (post-menopausal) with early stage breast cancer will benefit from bisphosphonate infusions (Zolendronate/Zometa) ranging from 6 monthly to 12 monthly for 3 years. There is a significant benefit in bone health, along with some improvement in breast cancer survival. Women with metastatic breast cancer, involving the bones will benefit from Denosumab/Xgeva injections or Zometa infusions. This is worth discussing with your Oncologist and General Practitioner. Global Cancer Statistics GLOBOCAN data (CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;1–35):

Global cancer statistics based on estimates from the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). There were close to 20 million new cases of cancer in the year 2022 (including nonmelanoma skin cancers [NMSCs]) alongside 9.7 million deaths from cancer (including NMSC). The estimates suggest that approximately one in five men or women develop cancer in a lifetime, whereas around one in nine men and one in 12 women die from it. Lung cancer was the most frequently diagnosed cancer in 2022, responsible for almost 2.5 million new cases, or one in eight cancers worldwide (12.4% of all cancers globally), followed by cancers of the female breast (11.6%), colorectum (9.6%), prostate (7.3%), and stomach (4.9%). Lung cancer was also the leading cause of cancer death, with an estimated 1.8 million deaths (18.7%), followed by colorectal (9.3%), liver (7.8%), female breast (6.9%), and stomach (6.8%) cancers. Breast cancer and lung cancer were the most frequent cancers in women and men, respectively (both cases and deaths). Incidence rates (including NMSC) varied from four‐fold to five‐fold across world regions, from over 500 in Australia/New Zealand (507.9 per 100,000) to under 100 in Western Africa (97.1 per 100,000) among men, and from over 400 in Australia/New Zealand (410.5 per 100,000) to close to 100 in South‐Central Asia (103.3 per 100,000) among women. I have several patients and families who travel while on treatment for cancer. I think it is great to travel and "get back to life". The thing of concern is that while people travel and get unwell on Australian soil - they could go to any hospital in Australia. The care and management would all be covered by Medicare or their private health insurance.

Getting unwell while overseas can be a completely different story. The cancer would most probably be considered a "pre-existing condition:" and not be covered by the travel health insurance. Medical care in some countries can be terribly expensive. It is also important to declare medical problems/conditions while filling out forms for travel health insurance. Standard medications for chemotherapy induced nausea include steroids - Dexamethasone, Metoclopramide or Domperidone, Palonosetron or Ondansetron, newer medications like Akynzeo. There are times when despite all this, nausea persists (not vomiting).

I have found that the best medication in these situations is Olanzapine. This is used primary for mental health problems like bipolar disorders, but is one of the best anti-nausea medications (chemotherapy induced). Anyone's death hurts. A young person's death - hurts even more. A young person's death whom you have cared for - hurts like anything.

I recently lost someone who I have cared for the past few years. Lovely person. Always joking around. Surrounded by a caring spouse and children. They were the person's universe. Diagnosing difficult and rare cancers makes it harder to find good treatment options. We struggled and managed to get access to expensive medications - via a free access program. I have to thank the pharmaceutical company who provided these medications for free. Once these medications stopped working - the cancer returned with a vengeance and life faded away. I think about the spouse and the little children. What would they do? What would they think? I think about all the unsaid things. I think about all the things which could not be done. Life can be brutal. Life can be tragic. We grieve. We learn. We keep caring. One of the possible side-effects of intravenous and tablet based chemotherapy or targeted therapies is diarrhoea. We encourage patients to use Loperamide tablets (Gastro-Stop) to treat and prevent diarrhoea. It works most times, but not always.

Diarrhoea is a adverse effect, which is not managed as well as we should. We have taken huge strides in the areas of vomiting and to some extent nausea, but diarrhoea has still not been tackled well enough. Some of my patients, who are on chemotherapy, and struggle with diarrhoea (not just the loose bowel motions, but the urgency and uncertainty of the bowel motions) - are scared to go out to public places. Like some of the them tell me - "when you go to go, you got to go now". I hunted for possible solutions and came across a free App called Flush - Flush app This has a database of toilet across the city and country towns. I am really not sure how they manage the database and if there is a way to update it in real time, but it surely has helped give some confidence to several of my patients. Seems like a silly problem?! Ask the person who is struggling with the issue. Poignant article from the ABC on this serious, yet not discussed about topic.

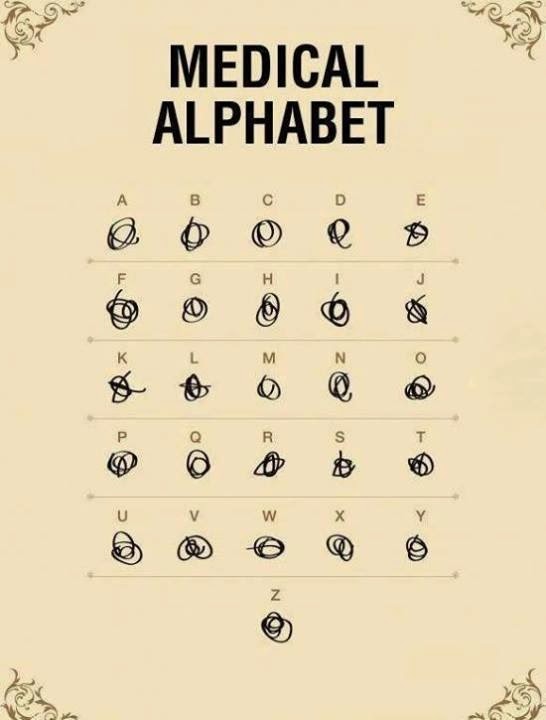

This is something which affects several people, yet not much information is available about this. Most people will not talk about it, as it is not the main issue. The problem is that this adds up to the rest of the stressors of life. Several relationships break down due to problems during or after cancer diagnosis and treatment. Worth discussing this in more detail with your cancer specialists. Cancer, Sex and Intimacy Several doctors write very poorly with regard to their handwriting. Some doctors who have a good handwriting seem to have missed their illegible handwriting course!!

I received this picture from a friend and am not sure about the origin of the picture (thus cannot acknowledge the author). Says it all. ps: I create a bit of a stir in clinic with patients and their families, as they watch me write quite legibly with a real fountain ink pen! A great indepth article in the BBC about Dr Hadiza Bawa-Garba, who was smashed with work load, responsibility, lack of support and then hung to dry. It worries many of us working in hospitals, because this could happen to any of us. Any time. The result could be the same.

The trainee doctor who took all the blame!! Learn to protect yourself. Learn to protect your colleagues and friends. Work together. Work safe. Each week in clinic, patients and their family members will bring me cut-outs from newspapers or magazines or video recorded clips from a TV article – mentioning about the latest and greatest cure for cancer. They bring the article will such hope and expectation. Rightly so.

The problem is that 90% of the times, I have to break their hopes by telling them that most of these reports are experiments are done in a laboratory test-tube or an early phase clinical trial. The chances of most of these drugs reaching a clinic is low or even if they do arrive, it would be at least 4 – 5 years. Most of the patients who need that medication now, will never get to use it. I understand that journalists have to publish interesting articles, but I really do hope that they would clearly state that this is experimental medication and might take several years to get to the clinic or something like that. Seems like a trivial issue, but it is a pretty big deal for patients and their family members who are struggling for anything new. The hope lives on. One of the possible side-effects of intravenous and tablet based chemotherapy or targeted therapies is diarrhoea. We encourage patients to use Loperamide tablets (Gastro-Stop) to treat and prevent diarrhoea. It works most times, but not always.

Diarrhoea is a adverse effect, which is not managed as well as we should. We have taken huge strides in the areas of vomiting and to some extent nausea, but diarrhoea has still not been tackled well enough. Some of my patients, who are on chemotherapy, and struggle with diarrhoea (not just the loose bowel motions, but the urgency and uncertainty of the bowel motions) - are scared to go out to public places. Like some of the them tell me - "when you go to go, you got to go now". I hunted for possible solutions and came across a free App called Flush - Flush app This has a database of toilet across the city and country towns. I am really not sure how they manage the database and if there is a way to update it in real time, but it surely has helped give some confidence to several of my patients. Seems like a silly problem?! Ask the person who is struggling with the issue. Nice article from the ABC by Elise Worthington. This highlights the issues with BRCA1 genes. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-05-07/worthington-deadly-decisions-women-and-the-cancer-gene/5432570 I think that the best true cancer chemotherapy reference website in the world is http://www.eviq.org.au It is a free registration for access, and gives you detailed information about chemotherapy regimes, protocols, patient information sheets, supportive care data, etc. Brilliant site. The spectrum of social issues explodes in some patients and their families. As you get to know the patient better and the family trust you, more details come out. Who is truly supportive, who is the true carer, who matters in the time of trouble, etc etc. Sad. Very sad most times. There are others, whom you would love to be a part of your family. They leave everything and are there for their parents or family or friends. Fantastic. A social worker’s job is quite phenomenal as they must be taking in all this stuff day-in-and-day-out. Wonder how they cope with this. Really. How do they cope with all this? Family matters. Stick close. The best research masterclass sessions in Oncology are:

# ACORD – Asia Pacific # Vail – USA # Flims – Europe If possible… attend one in a lifetime. Will change your perspective of research and analysis. How many doctors or nurses pray with their patients? Not many, but there are some who do so. Most doctors either do not think it to be important, are not convinced or are worried about the system. I need to start praying with my patients and their families. There are so many reports of the peace and the calm which is brought in. Found a great book called ” Gray Matter: A Neurosurgeon Discovers the Power of Prayer… One Patient at a Time” by David Levy and Joel Kilpatrick. Worth a read. Gray-Matter If I do not pray with the patient and their families, at least I should at least pray for them. In the setting of incurable cancer… over time most of us learn about the more important things versus the not-so-important things. Hugs from grandchildren are more important than the possible risk of infections…. an overseas holiday is more important than completing that last infusion of chemotherapy.

It is so important to take a proper social history – who is at home with the patient, spouse (lives along or not), who supports the patient. Do children support their parents – or just weekend hellos? We learn over time that we as humans take social issues to be vital. Research seems simple to do. We read about it daily… someone has found something somewhere, etc etc etc. Learning to do a proper research in a scientific manner is a completely different ball game.

One of the best learning experiences I had was at the ACORD workshop – Australia and Asia Pacific Clinical Oncology Research Development Workshop. This is held every two years in Queensland, Australia for seven days. Each of the applicants submit a concept which is evaluated by a panel and 70 participants are selected. The workshop teaches us to take the concept and develop it into a proper protocol, complete with statistics and everything needed to launch a study. Absolutely phenomenal. Keep looking out for the future dates. Where do we stand as far as social media is concerned? How many doctors/nurses have accounts for Facebook, Twitter, Pinterest, MySpace, etc, etc etc? More importantly how many doctors/nurses have been contacted by patients, their friends or relatives to become “friends”.

Where does the line of professionalism and personal info blur? I think this is dangerous. Be very careful. Most hospitals in Australia would not want staff to have social media accounts giving or discussing information about patients or about the hospital activity. Social media is a great source of engagement and information with friends and family. Stick with that 🙂 One of the hardest things for me as a doctor to to tell the patient and family that there is no more active treatment available. The simplest thing is usually to keep giving some treatment or the other. The harder thing is to say NO.

For most patients and their families – ongoing treatment means ongoing hope (however small it may be). When we say no, we are dashing that hope. There are ways to dilly dally with words and talk about best supportive care and symptom management and stuff like that. Hard decisions. Hard implementation. One of the most frustrating things in the clinic is meeting with patients and their families who refuse standard proven treatment in favour of options which may not have any logical or scientific basis.

It gets worse when the cancer is completely curable with standard treatment. Most of us can reason with patients to an extent, after which it is their call. Their life. Their responsibility. Or is it? Do we as a medical community need to increase awareness about wrong information being dissipated amongst patients and their families? Or do we already have enough work than to spend time on this. This is a relatively small proportion of patients who are so extreme. Should we just leave them to their thoughts and ideas? Recently I met a lady who had a breast mass but refused all treatment including a biopsy. After lots of chatting, she told me that her spiritual leader had not given her permission for treatment. We negotiated and ultimately she agreed that God has given us common sense. Prayer is vital for everything. We also need to use our brains for decisions. She agreed for treatment in the end. “Dr Web-browser” seems to have the answers. Depends on what we are looking for. Look Good Feel Better – http://www.lgfb.org.au

For patients with cancer who feel dreadful about their appearance, this workshop is great. I personally think that it is not so much for the make-up and cosmetics that help them…. as much as the fellowship of knowing that there are so many other people in the same boat as them. Massive boost to their esteem and confidence. This is an initiative of the Australian cosmetic industry for cancer patients in Australia. A definite suggestion to patients. from http://www.lgfb.org.au |

Rohit JoshiCancer, Medicine and Life: A cancer and medicine blog to help on the journey of life. Medicine and Medical Oncology are rapidly changing fields and is hard for most people to keep up. A diagnosis of any illness, in particular cancer is devastating news for anyone, and the hope is that we can share knowledge and support each other. Archives

May 2024

Categories

All

|

Created and nurtured by RJ & JJ

RSS Feed

RSS Feed